Ultramercial sued Hulu, YouTube, and WildTangent for infringement of U.S. Patent No. 7,346,545. The software patent generally relates to method for inserting ads in free online videos so that viewers must watch them before they can proceed. Hulu and YouTube were eventually dismissed from the case. WildTangent filed a

12(b)(6) motion to dismiss for failure to state a claim. The District Court for the Central District of California held that the patent does not

claim patent-eligible subject matter. On appeal, the Federal Circuit

reversed and remanded. However, that decision was vacated by the

Supreme Court.

Claim 1 recites:

A method for distribution of products over the Internet via a facilitator, said method comprising the steps of:

a first step of receiving, from a content provider, media

products that are covered by intellectual property rights protection and

are available for purchase, wherein each said media product being

comprised of at least one of text data, music data, and video data;

a second step of selecting a sponsor message to be associated

with the media product, said sponsor message being selected from a

plurality of sponsor messages, said second step including accessing an

activity log to verify that the total number of times which the sponsor

message has been previously presented is less than the number of

transaction cycles contracted by the sponsor of the sponsor message;

a third step of providing the media product for sale at an Internet website;

a fourth step of restricting general public access to said media product;

a fifth step of offering to a consumer access to the media

product without charge to the consumer on the precondition that the

consumer views the sponsor message;

a sixth step of receiving from the consumer a request to view

the sponsor message, wherein the consumer submits said request in

response to being offered access to the media product;

a seventh step of, in response to receiving the request from

the consumer, facilitating the display of a sponsor message to the

consumer;

an eighth step of, if the sponsor message is not an

interactive message, allowing said consumer access to said media product

after said step of facilitating the display of said sponsor message;

a ninth step of, if the sponsor message is an interactive

message, presenting at least one query to the consumer and allowing said

consumer access to said media product after receiving a response to

said at least one query;

a tenth step of recording the transaction event to the

activity log, said tenth step including updating the total number of

times the sponsor message has been presented;

and

an eleventh step of receiving payment from the sponsor of the sponsor message displayed.

Judge Rader noted first that it will be rare that a patent infringement suit can be dismissed at the pleading stage for lack of patentable subject matter. This is so because every issued

patent is presumed to have been issued properly, absent “clear and convincing” evidence to the contrary. Second, the analysis under § 101, while ultimately a legal determination, is rife with underlying factual issues. Third, and in part because of the factual issues involved,

claim construction normally will be required. Fourth, the question of eligible subject matter

must be determined on a claim-by-claim basis.

The court then noted that 35 U.S.C. § 101 sets forth the categories of subject matter that are eligible for patent protection:

“[w]hoever invents or discovers any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof, may obtain a patent therefor, subject to the conditions and requirements of this title.” Underscoring its breadth, § 101 both uses expansive categories and modifies them with the word “any.” In Bilski, the Supreme Court emphasized that “[i]n choosing such expansive terms modified by the comprehensive ‘any,’ Congress plainly contemplated that the patent laws would be given wide scope.” 130 S. Ct. at 3225 (quoting Diamond v. Chakrabarty, 447 U.S. 303, 308 (1980)).

The Supreme Court has on occasion recognized narrow judicial exceptions to the 1952 Act’s deliberately broadened eligibility provisions. In line with the broadly permissive nature of § 101’s subject matter eligibility principles and the structure of the Patent Act, case law has recognized only three narrow categories of subject matter outside the eligibility bounds of § 101—laws of

nature, physical phenomena, and abstract ideas. Bilski, 130 S. Ct. at 3225. The Court’s motivation for recognizing exceptions to this broad statutory grant was its desire to prevent the “monopolization” of the “basic tools of scientific and technological work,” which “might tend to impede innovation more than it would tend to promote it.” Mayo Collaborative Servs. v. Prometheus Labs., Inc., 132 S. Ct.

1289, 1293 (2012) (“Prometheus”)

Though recognizing these exceptions, the Court has also recognized that these implied exceptions are in obvious tension with the plain language of the statute, its history, and its purpose. Thus, this court must not read § 101 so restrictively as to exclude “unanticipated inventions” because the most

beneficial inventions are “often unforeseeable.”

In the eligibility analysis as well, the presumption of proper issuance applies to a granted software patent.

Defining “abstractness” has presented difficult problems, particularly for the § 101 “process” category. Clearly, a process need not use a computer, or some machine, in order to avoid “abstractness.” In this regard, the Supreme Court recently examined the statute and found that the ordinary, contemporary, common meaning of “method” may include even methods of doing business.

See Bilski, 130 S. Ct. at 3228. Accordingly, the Supreme Court refused to deem business methods ineligible for patent protection and cautioned against “read[ing] into the patent laws limitations and conditions which the legislature has not expressed.” Id. at 3226 (quoting Diamond v. Diehr, 450 U.S. 175, 182 (1981)).

In an effort to grapple with this non-statutory “abstractness” exception to “processes,” the dictionary provides some help. Judge Rader referred to Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate

Dictionary 5 (11th ed. 2003) (defining abstract as “disassociated from any specific instance . . . expressing a quality apart from an object ”). An abstract idea is one that has no reference to material objects or specific examples—i.e., it is not concrete.

He noted that members of both the Supreme Court and the Federal Circuit have recognized the difficulty of providing a precise formula or definition for the abstract concept of abstractness.

A software patent claim can embrace an abstract idea and be patentable. See Prometheus, 132 S. Ct. at 1294 (explaining that the fact that a claim uses a basic tool does not mean it is not eligible for patenting). Instead, a claim is not patent eligible only if, instead of claiming an application of an abstract idea, the claim is instead to the abstract idea itself.

In determining on which side of the line the software patent claim falls, the court must focus on the claim as a whole.

The Court has long-recognized that any software patent claim can be stripped down, simplified, generalized, or paraphrased to remove all of its concrete limitations, until at its core, something that could be characterized as an abstract idea is revealed. A court cannot go hunting for abstractions by

ignoring the concrete, palpable, tangible limitations of the invention the patentee actually claims.

Instead, the relevant inquiry is whether a claim, as a whole, includes meaningful limitations restricting it to an application, rather than merely an abstract idea. See Prometheus, 132 S. Ct. at 1297.

Judge Rader then considered an old example. The claims in O’Reilly v. Morse, 56 U.S. (15 How.) 62 (1854), and a case described therein, illustrate the distinction between a patent ineligible abstract idea and a practical application of an idea. The “difficulty” in Morse arose with the claim in which Morse did not propose to limit himself to the specific machinery or parts of machinery described in the specification and claims; the essence of him invention being the use of the motive power of the electric or galvanic current however developed for marking or printing intelligible characters, signs, or letters, at any distances. In considering Morse’s claim, the Supreme Court referred to an earlier English case that distinguished ineligible claims to a “principle” from claims “applying” that principle.

The Supreme Court repeatedly has cautioned against conflating the analysis of the conditions of patentability in the Patent Act with inquiries into patent eligibility. See Diehr, 450 U.S. at 190.

When assessing computer implemented claims, while the mere reference to a general purpose computer will not save a method claim from being deemed too abstract to be patent eligible, the fact

that a claim is limited by a tie to a computer is an important indication of patent eligibility. See Bilski, 130 S. Ct. at 3227. This tie to a machine moves it farther away from a claim to the abstract idea itself. Moreover, that same tie makes it less likely that the claims will pre-empt all practical applications of the idea.

This inquiry focuses on whether the claims tie the otherwise abstract idea to a specific way of doing something with a computer, or a specific computer for doing something; if so, they likely will be patent eligible. On the other hand, software patent claims directed to nothing more than the idea of doing that thing on a computer are likely to face larger problems. While no particular type of limitation is necessary, meaningful limitations may include the computer being part of the solution, being integral to the performance of the method, or containing an improvement in computer technology. See SiRF Tech., Inc. v. Int’l Trade Comm’n, 601 F.3d 1319, 1332-33 (Fed. Cir. 2010) (noting that “a machine,” a GPS receiver, was “integral to each of the claims at issue” and “place[d] a meaningful limit on

the scope of the claims”). A special purpose computer, i.e., a new machine, specially designed to implement a process may be sufficient. See Alappat, 33 F.3d at 1544.

In this case, the defending parties proceed on the assumption that the mere idea that advertising can be used as a form of currency is abstract, just as the vague, unapplied concept of hedging

proved patent-ineligible in Bilski.

The ’545 patent seeks to remedy problems with prior art banner advertising over the Internet, such as declining click-through rates, by introducing a method of product distribution that forces consumers to view and possibly even interact with advertisements before permitting access to the desired media product.

By its terms, the claimed invention invokes computers and applications of computer technology.

Specifically, the ’545 patent claims a particular internet and computer-based method for monetizing copyrighted products, consisting of the following steps: (1) receiving media products from a copyright holder, (2) selecting an advertisement to be associated with each media product, (3) providing said media products for sale on an Internet website, (4) restricting general public access to the media products, (5) offering free access to said media products on the condition that the consumer view the advertising, (6) receiving a request from a consumer to view the advertising, (7) facilitating the display of advertising and any required interaction with the advertising, (8) allowing the consumer access to the associated media product after such display and interaction, if any, (9) recording this transaction in an activity log, and (10) receiving payment from the advertiser. ’545 patent col. 8, ll. 5-48. Judge Rader noted that his court does not need the record of a formal claim construction to see that many of these steps require intricate and complex computer programming.

Even at this general level, it wrenches meaning from the word to label the claimed invention “abstract.” The claim does not cover the use of advertising as currency disassociated with any specific application of that activity. It was error for the district court to strip away these limitations and instead imagine some “core” of the invention.

Further, and even without formal claim construction, it is clear that several steps plainly require that the method be performed through computers, on the internet, and in a cyber-market environment. One clear example is the third step, “providing said media products for sale on

an Internet website.” Col. 8, ll. 20-21. And, of course, if the products are offered for sale on the Internet, they must be “restricted”—step four—by complex computer programming as well.

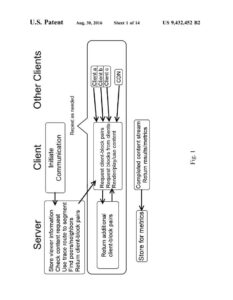

In addition, Figure 1, alone, demonstrates that the claim is not to some disembodied abstract idea but is instead a specific application of a method implemented by several computer systems, operating in tandem, over a communications network. Almost all of the steps in this process, as explained in the flow chart of Figure 2, are tied to computer implementation.

Viewing the subject matter as a whole, the invention involves an extensive computer interface. Unlike Morse, the claims are not made without regard to a particular process. Likewise, it does not say “sell advertising using a computer,” and so there is no risk of preempting all forms of advertising, let alone advertising on the Internet.

Further, the record at this stage shows no evidence that the recited steps are all token pre- or post-solution steps.

Finally, the software patent claim appears far from over generalized, with eleven separate and specific steps with many limitations and sub-steps in each category. The district court improperly made a subjective evaluation that these limitations did not meaningfully limit the “abstract idea at the

core” of the claims.

Having said that, the Federal Circuit refused to define the level of programming complexity required before a computer implemented method can be patent-eligible. Nor did the court hold that use of an Internet website to practice such a method is either necessary or sufficient in every case to satisfy § 101. They simply held the claims in this case to be patent-eligible, in this posture, in part because

of these factors.

At the pleadings stage, all that is required to survive a motion to dismiss based on Alice are plausible allegations in a complaint that the claims are patent-eligible.

At the pleadings stage, all that is required to survive a motion to dismiss based on Alice are plausible allegations in a complaint that the claims are patent-eligible.