The ITC took 35 U.S.C. § 101 to its logical extreme in this case, finding that diamond drill bits with certain physical measures are not patent-eligible.

The ITC took 35 U.S.C. § 101 to its logical extreme in this case, finding that diamond drill bits with certain physical measures are not patent-eligible.

The U.S. International Trade Commission conducts unfair import investigations that, most often, involve claims regarding intellectual property rights. US Synthetic Corporation filed an ITC complaint alleging violations based upon the importation into the United States of certain polycrystalline diamond compacts and articles infringing U.S. Patent Nos. 10,507,565, 10,508,502, and 8,616,306; and U.S. Patent Nos. 9,932,274 and 9,315,881. An Administrative Law Judge found at least one accused product infringes all asserted claims of the Asserted Patents, but that those claims are patent ineligible under 35 U.S.C. § 101 and/or invalid under 35 U.S.C. § 102.

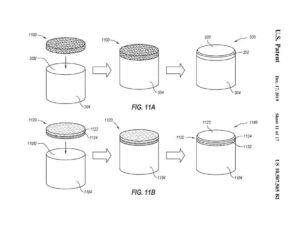

The technology in the patents relates to polycrystalline diamond compacts (“PDCs”), which are compacts made of a polycrystalline diamond (“PCD”) and a substrate. PDCs can be shaped as cylindrical parts.

In one disclosed embodiment, the PDC includes “a superabrasive diamond layer commonly referred to as a diamond table” or “PCD table,” a working surface of the PCD table, and a substrate. The substrate is often made from a cemented hard metal composite, like cobalt-cemented tungsten carbide. At least a portion of the PCD table includes a plurality of diamond grains defining a plurality of interstitial regions. The plurality of interstitial regions may be occupied by a metal-solvent catalyst, such as iron, nickel, cobalt, or alloys of any of the foregoing metals. The plurality of diamond grains may exhibit an average grain size of about 50 μm or less, such as about 30 μm or less or about 20 μm or less.

Conventional PDCs were fabricated by placing the substrate into a cartridge with a volume of diamond particles next to the substrate. This cartridge may be loaded into a press that creates high pressure and high-temperature (“HPHT”) conditions. The substrate and diamond particles are processed under the HPHT conditions in the presence of a catalyst material (e.g., from the substrate) that causes the diamond particles to bond to one another, creating a PCD table that is bonded to the substrate.

The inventors’ believed that the disclosed embodiments of PCDs sintered at a pressure of “at least about 7.5 GPa” differ from conventional HPHT products because they may promote a high-degree of diamond-to-diamond bonding.

PDCs can be used in drilling tools (e.g., cutting elements, gage trimmers, etc.), machining equipment, bearing apparatuses, wire-drawing machinery, and in other mechanical apparatuses. PDCs have found particular utility in cutters in rotary drill bits. A PDC with higher diamond-to-diamond bonding allows wear parts, such as drill bits, to last longer and perform better in high-abrasion applications, such as earth-boring.

Independent claims 1 of the ’565 patent is representative and reads as follows:

1. A polycrystalline diamond compact, comprising:

- a polycrystalline diamond table, at least an unleached portion of the polycrystalline diamond table including:

- a plurality of diamond grains directly bonded together via diamond-to-diamond bonding to define

interstitial regions, the plurality of diamond grains exhibiting an average grain size of about 50 μm or

less; - a catalyst occupying at least a portion of the interstitial regions;

- wherein the unleached portion of the polycrystalline diamond table exhibits a coercivity of about 115 Oe or more;

- wherein the unleached portion of the polycrystalline diamond table exhibits an average electrical conductivity of less than about 1200 S/m; and

- wherein the unleached portion of the polycrystalline diamond table exhibits a Gratio of at least about

4.0×106; and

- a plurality of diamond grains directly bonded together via diamond-to-diamond bonding to define

- a substrate bonded to the polycrystalline diamond table.

If you have read any of the other posts in Malhotra Law Firm’s History of Software Patents, you will be well aware that the Supreme Court has set forth a two-step framework for analyzing patent eligibility in Alice Corp. Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank Int’l, First, in Alice Step 1, the Federal Circuit is to determine whether the claims at issue are directed to patent-ineligible concepts such as laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas. If so, in Alice Step 2, the Federal Circuit is to examine the elements of each claim, considered both individually and as an ordered combination, for an “inventive concept” sufficient to transform the nature of the claim into a patent eligible application.

The ITC stated that it is clear from the language of the claims that the claims involve an abstract idea—namely, the abstract idea of a PDC that achieves the claimed performance measures (G-Ratio and thermal stability) and has certain measurable side effects (specific magnetic saturation, coercivity, and specific permeability), which, as discussed below, the specifications posit are derived from enhanced diamond-to-diamond bonding in the PCDs. Gratio and thermal stability are performance measurements (specifically of a PDC’s wear resistance and thermal properties), which the specifications posit may be derived from

stronger diamond-to-diamond bonding.

As for the electrical and magnetic properties of a PCD, the ITC stated that there is no dispute that the presence of cobalt or other metal-solvent catalyst in the PCD is measurable. However, electrical and magnetic properties are not design choices or manufacturing variables, but are instead indirect measures of the effectiveness of other design choices and manufacturing variables, such as sintering pressure, temperature, metal content, and grain size, none of which,

besides grain size, are recited in the claims.

There was a dissenting view that the fact that the claimed characteristics of PDCs may be measured makes the claims less abstract for purposes of Alice. However, according to the majority, the Federal Circuit has explained that the patent eligibility inquiry requires that the claim identify how a functional result is achieved by limiting the claim scope to structures specified at some level of concreteness, in the case of a product claim, or to concrete action, in the case of a method claim.”

Alice rejections are thought to only be an issue for software and biotech inventions. Patent practitioners who practice outside these areas may not seriously consider that Alice issues could become a problem. They would be well advised to study the logic behind cases like this. That is true even though one would be forgiven for believing that diamond drill bits or other compositions of matter are too abstract. Alice rejections are based on an exception to the rule of 35 USC 101: Whoever invents or discovers any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof, may obtain a patent therefor, subject to the conditions and requirements of this title. However, the exception can swallow the rule if interpreted broadly enough. The problem with characterizing something as “Abstract” in Alice step 1 is that it inherently requires summarizing a claim or ignoring details in a claim. Anything can be characterized as abstract if enough limitations in a claim are ignored. If accused of patent infringement, Alice challenges to validity should always be considered. This is particularly true with broad claims that recite a desired result without much detail of how to achieve the result. If you need help protecting your software or coming up with a strategy to defend against a claim of infringement, contact Malhotra Law Firm, PLLC.