Multilevel security claims were patent eligible because they were directed to solving a technical problem specific to computer network security. The district court correctly rejected Adobe’s ineligibility challenge.

Multilevel security claims were patent eligible because they were directed to solving a technical problem specific to computer network security. The district court correctly rejected Adobe’s ineligibility challenge.

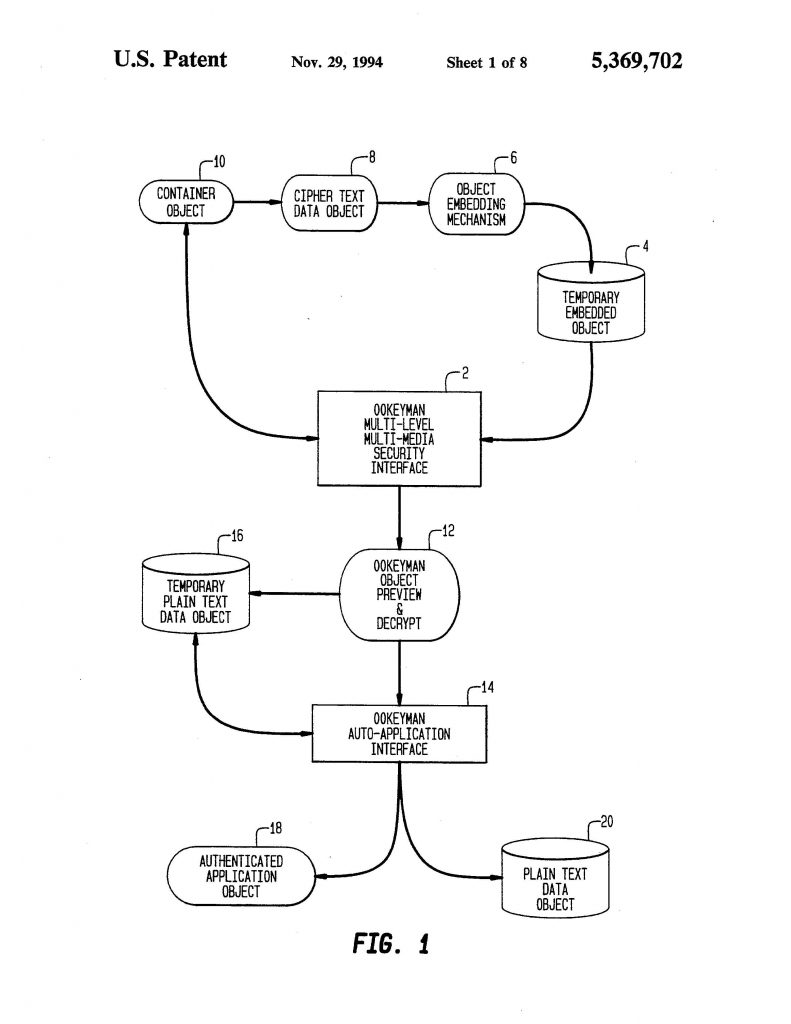

TecSec owns U.S. Patent Nos. 5,369,702, 5,680,452, 5,717,755, and 5,898,781, the patents involved in this case. The patents are entitled “Distributed Cryptographic Object Method” (“DCOM”) and claim particular systems and methods for multi-level security of various kinds of files being transmitted in a data network. The DCOM patents describe a method in which a digital object—e.g., a document, video, or spreadsheet—is assigned a level of security that corresponds to a certain combination of access controls and encryption. The encrypted object can then be embedded or “nested” within a “container object,” which, if itself encrypted and access-controlled, provides a second layer of security.

U.S. Patent No. 5,369,702

Claim 1 of U.S. Patent No. 5,369,702 is representative of the asserted claims and recites:

A method for providing multi-level multimedia security in a data network, comprising the steps of:

- A) accessing an object-oriented key manager;

- B) selecting an object to encrypt;

- C) selecting a label for the object;

- D) selecting an encryption algorithm;

- E) encrypting the object according to the encryption algorithm;

- F) labelling the encrypted object;

- G) reading the object label;

- H) determining access authorization based on the object label; and

- I) decrypting the object if access authorization is granted.

Alice v CLS Two Step Test

35 U.S.C. § 101 contains an important implicit exception: Laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas are not patentable. Alice Corp. Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank Int’l. In Alice, the Supreme Court explained that a “claim falls outside § 101 where (1) it is ‘directed to’ a patent-ineligible concept, i.e., a law of nature, natural phenomenon, or abstract idea, and (2), if so, the particular elements of the claim, considered ‘both individually and “as an ordered combination,”’ do not add enough to ‘“transform the nature of the claim” into a patent-eligible application.’”

The Federal Circuit We has approached the Step 1 “directed to” inquiry by asking “what the patent asserts to be the ‘focus of the claimed advance over the prior art. And the Federal Circuit has reiterated the Supreme Court’s caution against “overgeneralizing claims” in the § 101 analysis, explaining that characterizing the claims at “a high level of abstraction” that is “untethered from the language of the claims all but ensures that the exceptions to § 101 swallow the rule.” Enfish

The Federal Circuit stated that, in cases involving software innovations, this inquiry often turns on whether the claims focus on specific asserted improvements in computer capabilities or instead on a process or system that qualifies an abstract idea for which computers are invoked merely as a tool. Software can make patent-eligible improvements to computer technology, and related claims are eligible as long as they are directed to non-abstract improvements to the functionality of a computer or network platform itself.

The Federal Circuit stated that they have found claims directed to such eligible matter in a number of cases where they made two inquiries of significance here: whether the focus of the claimed advance is on a solution to “a problem specifically arising in the realm of computer networks” or computers, as in DDR v Hotels.com, and whether the claim is properly characterized as identifying a “specific” improvement in computer capabilities or network functionality, rather than only claiming a desirable result or function, Uniloc v LG Electronics.

Alice Step 1

The Step 1 “directed to” analysis called for by the cases depends on an accurate characterization of what the claims require and of what the patent asserts to be the claimed advance. Unfortunately, a case can turn out either way depending on whether the Federal Circuit decides to characterize a claim as being directed to an abstract concept.

Adobe argued to the district court that “the claims are directed to the impermissibly abstract idea of managing access to objects using multiple levels of encryption.” But that characterization of the representative claims is materially inaccurate. To arrive at it, Adobe had to disregard elements of the claims at issue that the specification makes clear are important parts of the claimed advance in the combination of elements. According to the Federal Circuit, It goes beyond managing access to objects using multiple levels of encryption, as required by “multi-level . . . security.” Notably, it expressly requires, as well, accessing an “object-oriented key manager” and specified uses of a “label” as well as encryption for the access management. To disregard those express claim elements is to proceed at “a high level of abstraction” that is “untethered from the claim language” and that overgeneralizes the claim.

According to the Federal Circuit, the specification elaborates in a way that simultaneously shows that the claims at issue are directed at solving a problem specific to computer data networks. The patent focuses on allowing for the simultaneous transmission of secure information to a large group of recipients connected to a decentralized network—an important feature of data networks—but without uniform access to all data by all recipients. The proposed improvement involves, among other things, labeling together with encryption. Using a secure labelling regimen, a network manager or user can be assured that only those messages meant for a certain person, group of persons, and/or location(s) are in fact received, decrypted, and read by the intended receiver.

Thus, the specification, as well as the claims, were used in determining whether the claims are directed to an impermissibly abstract idea.

This kind of analysis arguably should have been performed in Alice Step 2, where the courts are supposed to determine if there is something substantially more than the abstract idea.

MULTI LEVEL SECURITY ISN’T ALWAYS ABSTRACT

The Federal Circuit went on to state that while non-computer settings may have security issues addressed by multilevel security, it does not follow that all patents relating to multilevel security are necessarily ineligible for patenting. Here, although the patent involves multilevel security, that does not negate the conclusion that the patent is aimed at solving a particular problem of multicasting computer networks.

By way of comparison, in Uniloc v LG Electronics, the Federal Circuit held the claims at issue to be directed to solving a problem of reducing communication time by using otherwise-unused space in a particular protocol-based system, even though reducing communication time by using such available blank space (or, generally, reducing resource use by using otherwise-unused available resources) is a goal in many settings.

Adobe came up with a new definition of what it considered to be the abstract idea. When Adobe discussed its formulation of the asserted abstract idea, it did not meaningfully address the combination. Rather, it asserted the “common-place” character of the individual component techniques generally. But that approach is insufficient where, as is true here for the reasons we have explained, it is the combination of techniques that is “what the patent asserts to be the focus of the claimed advance over the prior art.”

The Federal Circuit concluded that the district court correctly rejected Adobe’s ineligibility challenge.

Thus, novelty comes into play. Contrary to what is considered to be proper practice, it may be worthwhile to have some discussion, in a patent application, of what combination of techniques may be novel, and how that improves problems in a system.