Functionally recited claims to organizing and displaying visual information are not patent-eligible.

Functionally recited claims to organizing and displaying visual information are not patent-eligible.

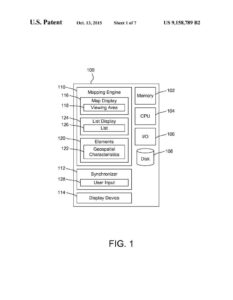

IBM owns U.S. Patent No. 9,158,789 on a software method for coordinated geospatial, list-based and filter-based selection. A user draws a shape on a map to select that area of the map, and the claimed system then filters and displays data limited to that area of the map. It synchronizes which elements are shown as “selected” on the map and its associated list.

Claim 8 is representative and recites:

8. A method for coordinated geospatial and list-based mapping, the

operations comprising:

- presenting a map display on a display device, wherein the map display comprises elements within a viewing area of the map display, wherein the elements comprise geospatial characteristics, wherein the elements comprise selected and unselected elements;

- presenting a list display on the display device, wherein the list display comprises a customizable list comprising the elements from the map display;

- receiving a user input drawing a selection area in the viewing area of the map display, wherein the selection area is a user determined shape, wherein the selection area is smaller than the viewing area of the map display, wherein the viewing area comprises elements that are visible within the map display and are outside the selection area;

- selecting any unselected elements within the selection area in response to the user input drawing the selection area and deselecting any selected elements outside the selection area in response to the user input drawing the selection area; and

- synchronizing the map display and the list display to concurrently update the selection and deselection of the elements according to the user input, the selection and deselection occurring on both the map display and the list display.

IBM also owns U.S. Patent No. 7,187,389, which describes methods of displaying layered data on a spatially oriented display (like a map), based on nonspatial display attributes (like visual characteristics—color hues, line patterns, shapes, etc.). Essentially, the ‘389 patent claims a method of displaying objects in visually distinct layers. Objects in layers of interest can be brought to and emphasized at the top of the display while other layers are deemphasized.

Claim 1 is representative and recites:

1. A method of displaying layered data, said method comprising:

- selecting one or more objects to be displayed in a plurality of layers;

- identifying a plurality of non-spatially distinguishable display attributes, wherein one or more of the non-spatially distinguishable display attributes corresponds to each of the layers;

- matching each of the objects to one of the layers;

- applying the non-spatially distinguishable display attributes corresponding to the layer for each of the matched objects;

- determining a layer order for the plurality of layers, wherein the layer order determines a display emphasis corresponding to the objects from the plurality of objects in the corresponding layers; and

- displaying the objects with the applied non-spatially distinguishable display attributes based upon the determination, wherein the objects in a first layer from the plurality of layers are visually distinguished from the objects in the other plurality of layers based upon the non-spatially distinguishable display attributes of the first layer.

Dependent claim 2 adds method steps for rearranging layers and rematching objects in layers based on a user request.

IBM filed this patent infringement suit against Zillow in 2019, alleging that Zillow infringed seven of IBM’s patents. Zillow filed a motion for judgment on the pleadings, arguing that the claims of four of IBM’s asserted patents were patent ineligible under § 101. The district court granted Zillow’s motion as to both the ‘389 and ‘789 patents, concluding that both were directed to abstract ideas, contain no inventive concept, and fail to recite patentable subject matter.

If you have read any of the other posts in Malhotra Law Firm’s History of Software Patents, you will be well aware that the Supreme Court has set forth a two-step framework for analyzing patent eligibility in Alice Corp. Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank Int’l, First, in Alice Step 1, the Federal Circuit is to determine whether the claims at issue are directed to patent-ineligible concepts such as laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas. If so, in Alice Step 2, the Federal Circuit is to examine the elements of each claim, considered both individually and as an ordered combination, for an “inventive concept” sufficient to transform the nature of the claim into a patent eligible application.

Regarding the ‘789 patent, beginning with Alice step one, the Federal Circuit agreed with the District Court that the claims here fail to recite any assertedly inventive technology for improving computers as tools, and are instead directed to an abstract idea for which computers are invoked merely as a tool. The claims are directed to limiting and coordinating the display of information based on a user selection.

According to the Federal Circuit, identifying, analyzing, and presenting certain data to a user is not an improvement specific to computing. Merely requiring the selection and manipulation of information—to provide a ‘humanly comprehensible’ amount of information useful for users ․ —by itself does not transform the otherwise abstract processes of information collection and analysis. This is a problem when trying to patent user interface designs. According to the Federal Circuit, the claims here recite similarly abstract steps: presenting a map, having a user select a portion of that map, and then synchronizing the map and its corresponding list to display a more limited data set to the user. Using a computer to “concurrently update” the map and the list may speed up the process, but “mere automation of manual processes using generic computers does not constitute a patentable improvement in computer technology.

Furthermore, a claim that merely describes an ‘effect or result dissociated from any method by which it is accomplished’ is usually not directed to patent-eligible subject matter. The Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that the ‘789 patent is result-oriented, describing required functions (presenting, receiving, selecting, synchronizing), without explaining how to accomplish any of the tasks. It is written in result-based functional language that does not sufficiently describe how to achieve these results in a non-abstract way. The claims and specification do not disclose a technical improvement or otherwise suggest that one was achieved. The Federal Circuit concluded that the ‘789 patent is directed to an ineligible abstract idea.

Turning to Alice step two, the Federal Circuit determined whether the claims do significantly more than simply describe the abstract method and thus transform the abstract idea into patentable subject matter.

When evaluating whether a complaint fails to state a claim (under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6)), only plausible and specific factual allegations that aspects of the claims are inventive are sufficient.

According to the Federal Circuit, IBM had not made plausible and specific allegations that any aspect of the claims is inventive. The cited “synchronizing” and “user determined shape” limitations use functional language, at a high level of generality and divorced from any computer technology, to recite the claimed functions. The limitations simply describe the abstract method without providing more. Even if they did require the use of a computer, claims toan abstract idea implemented on generic computer components, without providing a specific technical solution beyond simply using generic computer concepts in a conventional way do not suffice at step two.

The Federal Circuit next turned to the ‘389 software patent, beginning with Alice step one.

The Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that the ‘389 patent is directed to the abstract idea of organizing and displaying visual information. They have held that the collection, organization, and display of two sets of information on a generic display device is abstract absent a ‘specific improvement to the way computers [or other technologies] operate. The ‘389 patent’s claims do not improve the functioning of the computer, make it operate more efficiently, or solve any technological problem. Instead, they recite a purportedly new arrangement of generic information that assists users in processing information more quickly.

Furthermore, like the ‘789 patent, the ‘389 patent describe[s] various operations (selecting, identifying, matching, re-matching, applying, determining, displaying, receiving, and rearranging), without explaining how to accomplish any of the tasks.

Such functional claim language, without more, is insufficient for patentability.

IBM argued that its claimed invention is like a software interface patent that the Federal Circuit held patentable in Core Wireless Licensing S.A.R.L. v. LG Electronics, Inc., because it is directed to particular or specific implementations of presenting information in electronic devices. Core Wireless involved a patent directed to “improved display interfaces” of electronic devices that “allow a user to more quickly access desired data stored in, and functions of applications included in, the electronic devices,” particularly those with small screens like mobile telephones. The Federal Circuit held that the asserted claims were directed to “an improved user interface for computing devices” that was patentable because it addressed problems specific to navigating applications on small screens, as repeatedly emphasized by the patent’s specification. The Federal Circuit concluded in that case that the specification’s “language clearly indicates that the claims are directed to an improvement in

the functioning of computers, particularly those with small screens.” Here, representative claim 1 of the ‘389 patent is much broader than the asserted claims in Core Wireless. It is not limited to computer screens or any device at all. The method it recites (selecting, organizing, and displaying visual information based on non-spatial attributes) has long been done by cartographers creating paper maps.

The problem the ‘389 patent purportedly solves—i.e., that the display of “any system that has large numbers of objects in many categories with relationships is difficult to understand,” ‘is not specific to a computing environment. One could encounter this same occlusion problem when looking at a particularly cluttered paper map. The patent’s solution—to visually present information in a way that aids the user in distinguishing between the various displayed layers,—could be accomplished using colored pencils and translucent paper, as the district court noted. The Federal Circuit thus concluded that the ‘389 patent is directed to an ineligible abstract idea and proceeded to Alice step two.

At Alice step two, the ‘389 patent fared no better. The district court concluded that the patent contained no inventive concept because it was not directed to a computer specific problem and merely used well-understood, routine, or conventional technology (a general-purpose computer) to more quickly solve the problem of layering and displaying visual data.

The Federal Circuit saw no inventive concept that transforms the abstract idea of organizing and displaying visual information into a patent-eligible application of that abstract idea.

Interfaces are tricky to patent after Alice. Design patent application should always be filed for computer graphics interfaces as a large percentage are allowed as filed and as litigation is less costly than for utility patents. Utility patents are possible if sufficient details are disclosed and claimed or if there is some argument that computer performance is improved. If you need help protecting your software, contact Malhotra Law Firm, PLLC.