It is bad enough that the Supreme Court doesn’t know what it is doing when it comes to software patents. In Alice v CLS, they considered a financial patent that could have easily been invalidated on the grounds of obviousness, and instead invalidated it based on subject matter (35 U.S.C. 101). They didn’t say that financial methods cannot be patented. They did not say that all software patents are invalid. They used a vague framework from a biotech decision. The courts now use an unclear test that involves considering whether the subject matter of the claim is “too abstract” and, if so, whether the claims add “significantly more”. Neither of these concepts were well defined. I suppose they were hoping for judicial efficiency in having courts decide that some patents were of subject matter types that aren’t worthy of claim construction or obviousness analyses.

We can forgive the Supreme Court. They are usually dealing with completely different types of cases. They have been waiting for congress to legislate since Gottschalk v. Benson in 1972.

The Federal Circuit, on the other hand, our court of appeals for patent cases, is supposed to have specialized knowledge of patent law. They were formed to bring consistency to the law, an improvement over the inconsistent decisions that were being issued from the various circuit courts of appeal, who were more experienced with criminal law than patent law.

But the Federal Circuit just can’t make up its mind on when software should or should not be patentable. After the recent decision in McRo, which seemed to be taking us towards a “technical effect,” European-style test, that also considers preemption and non-obviousness (as I had predicted when I wrote my summary of Alice v CLS), we get Intellectual Ventures v Symantec. The main opinion, by Judge Dyk, isn’t entirely unreasonable, but just wait until you read Judge Mayer’s concurrence (summarized below, after the discussion of the opinion).

Intellectual Ventures I LLC (“IV”) sued Symantec Corp. and Trend Micro for infringement of various claims of U.S. Patent Nos. 6,460,050, 6,073,142, and 5,987,610. The district court held the asserted claims of the ’050 patent and the ’142 patent to be ineligible under § 101, and the asserted claim of the ’610 patent to be eligible. The Federal Circuit didn’t find any asserted claims to be patent-eligible.

Intellectual Ventures I LLC (“IV”) sued Symantec Corp. and Trend Micro for infringement of various claims of U.S. Patent Nos. 6,460,050, 6,073,142, and 5,987,610. The district court held the asserted claims of the ’050 patent and the ’142 patent to be ineligible under § 101, and the asserted claim of the ’610 patent to be eligible. The Federal Circuit didn’t find any asserted claims to be patent-eligible.

Claim 9 is representative of the ‘050 patent:

9. A method for identifying characteristics of data files, comprising:

- receiving, on a processing system, file content identifiers for data files from a plurality of file content identifier generator agents, each agent provided on a source system and creating file content IDs using a mathematical algorithm, via a network;

- determining, on the processing system, whether each received content identifier matches a characteristic of other identifiers; and

- outputting, to at least one of the source systems responsive to a request from said source system, an indication of the characteristic of the data file based on said step of determining.

The Federal Circuit agreed with the lower court that filtering files/e-mail—is an abstract idea. Looking a bit at the obviousness question, and conflating 103 and 101 like the Supreme Court did in Alice v CLS, the Federal Circuit stated that it was long-prevalent practice for people receiving paper mail to look at an envelope and discard certain letters, without opening them, from sources from which they did not wish to receive mail based on characteristics of the mail. The list of relevant characteristics could be kept in a person’s head. Characterizing e-mail based on a known list of identifiers is no less abstract. The patent merely applies a well-known idea using generic computers “to the particular technological environment of the Internet.”

The Federal Circuit then proceeded to the Mayo/Alice step two to determine whether the claims contain an “inventive concept” that renders them patent-eligible.

The Federal Circuit noted that Indeed, “[t]he ‘novelty’ of any element or steps in a process, or even of the process itself, is of no relevance in determining whether the subject matter of a claim falls within the § 101 categories of possibly patentable subject matter”, quoting Diamond v. Diehr, 450 U.S. 175, 188–89 (1981).

They also cite the Mayo Supreme Court decision for a rejection of the Government’s invitation to substitute §§ 102, 103, and 112 inquiries for the better established inquiry under § 101. Better established? Really?

The Federal Circuit notes that the steps of the asserted claims of the ’050 patent do not “improve the functioning of the computer itself.” This gives us a big hint on how to draft software patent applications in the future. Look for ways that the software is improving the computer. Perhaps less memory is being used.

IV argued that the ’050 patent “shrink[s] the protection gap and moot[s] the volume problem.” According to IV, the protection gap is “the period of time between identification of a computer

virus by an anti-malware provider and distribution of that knowledge to its users.” The volume problem is the “exponential growth in malware and spam,” increasing the amount of antivirus signatures to be downloaded. However, the asserted claims do not contain any limitations that address the protection gap or volume problem, e.g., by requiring automatic updates to the

antivirus or antispam software or the ability to deal with a large volume of such software. So a practice pointer is to be sure to add limitations to the claims that solve a technological problem.

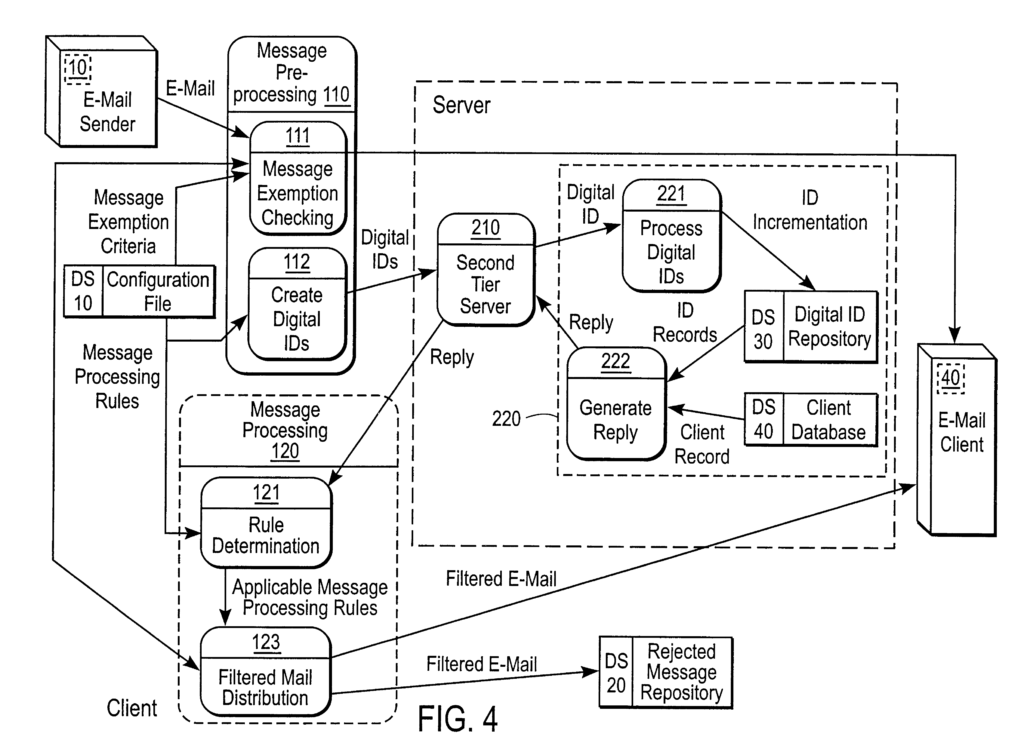

Claim 1 is representative of how the ’142 patent screens e-mail, and recites:

1. A post office for receiving and redistributing email messages on a computer network, the post

office comprising:

- a receipt mechanism that receives an e-mail message from a sender, the e-mail message having at least one specified recipient;

- a database of business rules, each business rule specifying an action for controlling the delivery of an e-mail message as a function of an attribute of the e-mail message;

- a rule engine coupled to receive an e-mail message from the receipt mechanism and coupled to the database to selectively apply the business rules to the e-mail message to determine from selected ones of the business rules a set of actions to be applied to the e-mail message; and

- a distribution mechanism coupled to receive the set of actions from the rule engine and apply at least one action thereof to the e-mail message to control delivery of the e-mail message and which in response to the rule engine applying an action of deferring delivery of the e-mail message, the distribution engine automatically combines the email message with a new distribution list specifying at least one destination post office for receiving the e-mail message for review by an administrator associated with the destination post office, and a rule history specifying the business rules that were determined to be applicable to the e-mail message by at least one rule engine, and automatically delivers the e-mail message to a first destination post office on the distribution list instead of a specified recipient of the e-mail message.

The district court held that the asserted claims of the ’142 software patent are directed to human practicable concepts, which could be implemented in, for example, a brick-and-mortar post office. The Federal Circuit agreed, and found the district court’s analogy to a corporate mailroom to also be useful.

IV itself informed the district court, in its technology tutorial, that in the typical environment, the post office resides on a mail server, where the company’s emails are received, processed, and routed to recipients. IV stupidly added that, conceptually, this post office is not much different than a United States Postal Service office that processes letters and packages, except that the process is all computer implemented and done electronically in a matter of seconds.

Again conflating 103 and 101 issues, the Federal Circuit found the concept to be well-known and abstract.

Proceeding to step 2, the Federal Circuit considered whether each step does no more than require a generic computer to perform generic computer functions as in Alice. They found that here, that is the case.

Claim 7 was is the only asserted claim of the ’610 patent. The district court held eligible claim 7 of the ’610 patent.

Claim 7 depends from claim 1, which provides:

1. A virus screening method comprising the steps

of:

- routing a call between a calling party and a called party of a telephone network;

- receiving, within the telephone network, computer data from a first party selected from the group consisting of the calling party and the called party;

- detecting, within the telephone network, a virus in the computer data; and

- in response to detecting the virus, inhibiting communication of at least a portion of the computer data from the telephone network to a second party selected from the group consisting of the calling party and the called party.

Claim 7 recites:

7. The virus screening method of claim 1 further comprising the step of determining that virus screening is to be applied to the call based upon at least one of an identification code of the calling party and an identification code of the called party.

Unlike the asserted claims of the ’050 and ’142 patents, claim 7 involves an idea that originated in the computer era—computer virus screening.

But the idea of virus screening was well known at the time the application was filed. Here again, 103 analysis creeps in to the 101 analysis. A sensible court would skip the 101 analysis altogether and just use obviousness analysis as the real test. But the Federal Circuit is stuck with the mess that the Supreme Court has created.

The Federal Circuit noted that virus screening is well-known and constitutes an abstract idea. At step two of Mayo/Alice, the Federal Circuit found no other aspect of the claim that is anything but conventional. They stated that just as performance of an abstract idea on the Internet is abstract, so too the performance of an abstract concept in the environment of the telephone network is abstract.

Nor does the asserted claim improve or change the way a computer functions. Claim 7 recites no more than generic computers that use generic virus screening technology.

Judge Meyer wrote separately to make his two points: (1) patents constricting the essential channels of online communication run afoul of the First Amendment; and (2) claims directed to software implemented on a generic computer are categorically not eligible for patent.

He wrote that the Constitution protects the right to receive information and ideas. . . . This right to receive information and ideas, regardless of their social worth, is fundamental to our free society, quoting the Supreme Court decision in Stanley v. Georgia. According to Judge Meyer, patents, which function as government-sanctioned monopolies, invade core First Amendment rights when they are allowed to obstruct the essential channels of scientific, economic, and political discourse.

According to Judge Mayer, although the claims at issue here disclose no new technology, they have the potential to disrupt, or even derail, large swaths of online communication. Suppression of free speech is no less pernicious because it occurs in the digital, rather than the physical, realm. “[W]hatever the challenges of applying the Constitution to ever-advancing technology, the basic principles of freedom of speech and the press, like the First Amendment’s command, do not vary when a new and different medium for communication appears.” Brown v. Entm’t Merchs. Ass’n.

According to Judge Meyer, like all congressional powers, the power to issue patents and copyrights is circumscribed by the First Amendment. Just as the idea/expression dichotomy and the fair use defense serve to keep copyright protection from abridging free speech rights, restrictions on subject matter eligibility can be used to keep patent protection within constitutional bounds. Section 101 creates a “patent-free zone” and places within it the indispensable instruments of

social, economic, and scientific endeavor. Section 101, if properly applied, can preserve the Internet’s open architecture and weed out those patents that chill political expression and impermissibly obstruct the marketplace of ideas.

According to Judge Meyer, most of the First Amendment concerns associated with patent protection could be avoided if the Federal Circuit were willing to acknowledge that Alice sounded the death knell for software patents.

The problem with Judge Meyer’s analysis is that you can’t have a marketplace without property rights. You would have cheap overseas versions of software that developers spent good money to develop. Software is one of the few industries in which the U.S. is a net exporter. Copyright is only effective for protecting against outright copies, not for protecting inventive concepts within software.

Yes, the Internet is an open framework as Judge Meyer notes. However, it started as ARPANET funded by the Department of Defense. Why would a private company put R&D money into a new technology and then give it away? Do we really want the government developing our software? That might be how things end up if the venture capital firms decide that they will not recoup their investments and if they stop investing in software startups. When you take away the profit motive for startups, you are left with government or consolidation by large multinationals that happily move jobs overseas. Well, maybe having the government develop software wouldn’t be all that bad. It couldn’t be worse than Windows 8.

Hopefully Judge Meyer will not be involved in writing too many software patent decisions.

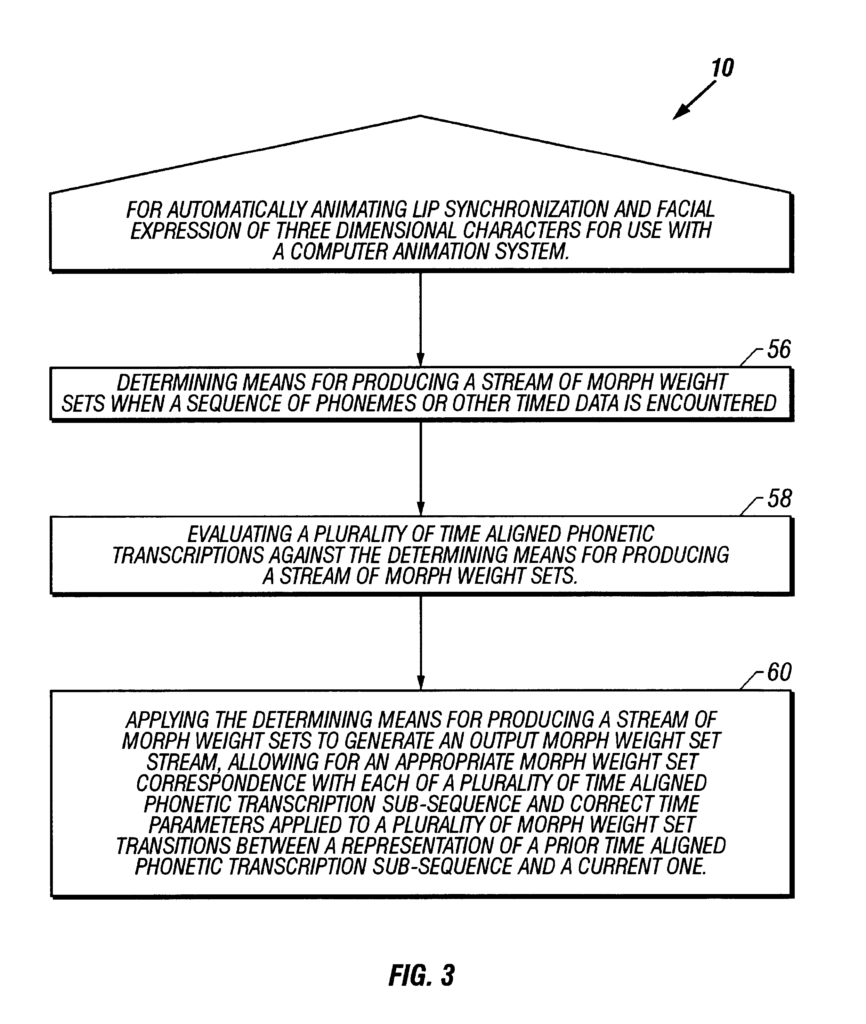

This was an appeal from a grant of judgment on the pleadings that the asserted claims of two software patents, U.S. Patent Nos. 6,307,576 (‘‘the ’576 patent’’) and 6,611,278 (‘‘the ’278 patent’’) were invalid.

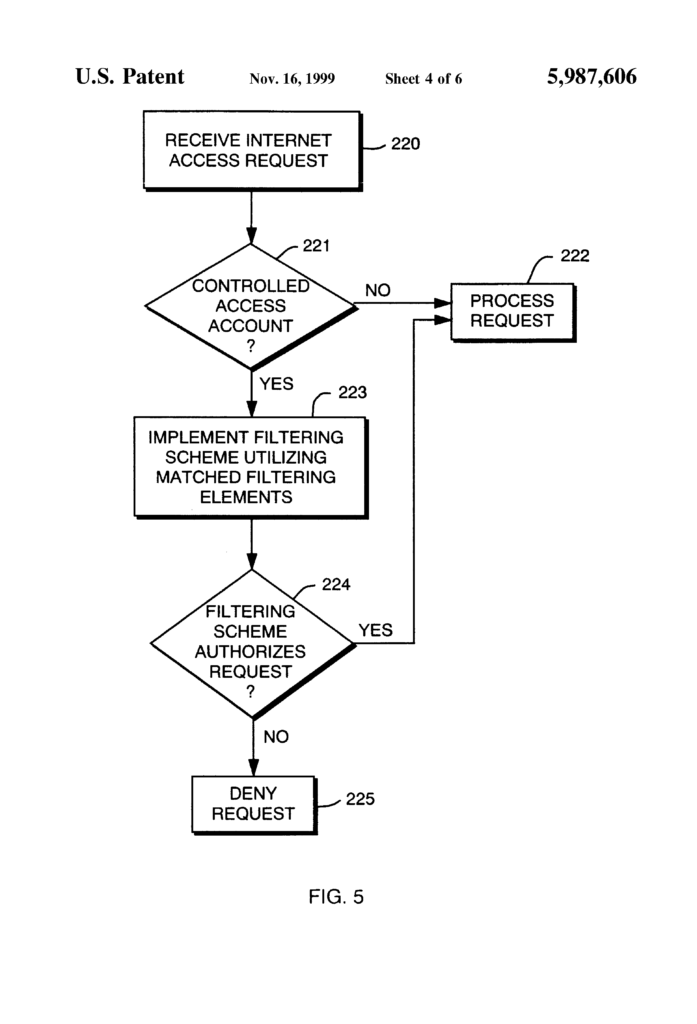

This was an appeal from a grant of judgment on the pleadings that the asserted claims of two software patents, U.S. Patent Nos. 6,307,576 (‘‘the ’576 patent’’) and 6,611,278 (‘‘the ’278 patent’’) were invalid. This was an appeal against a district court decision that the claims of U.S. Patent No. 5,987,606 are invalid as a matter of law under 35 U.S.C. § 101.

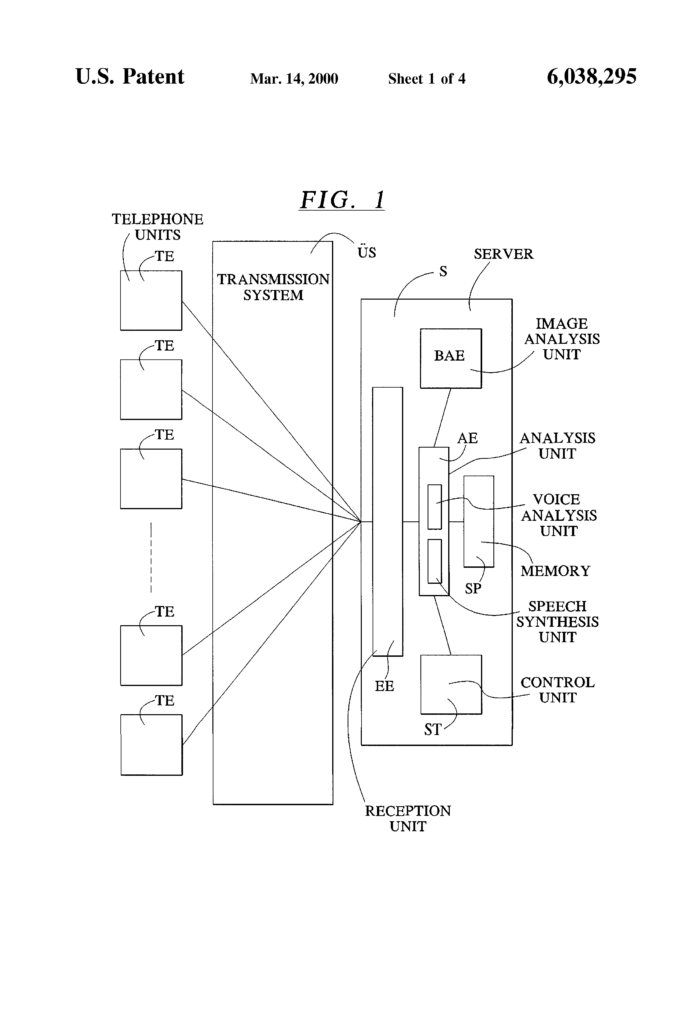

This was an appeal against a district court decision that the claims of U.S. Patent No. 5,987,606 are invalid as a matter of law under 35 U.S.C. § 101. TLI Communications hold U.S. Patent No. 6,038,295 relating to a method and system for taking, transmitting, and organizing digital images.

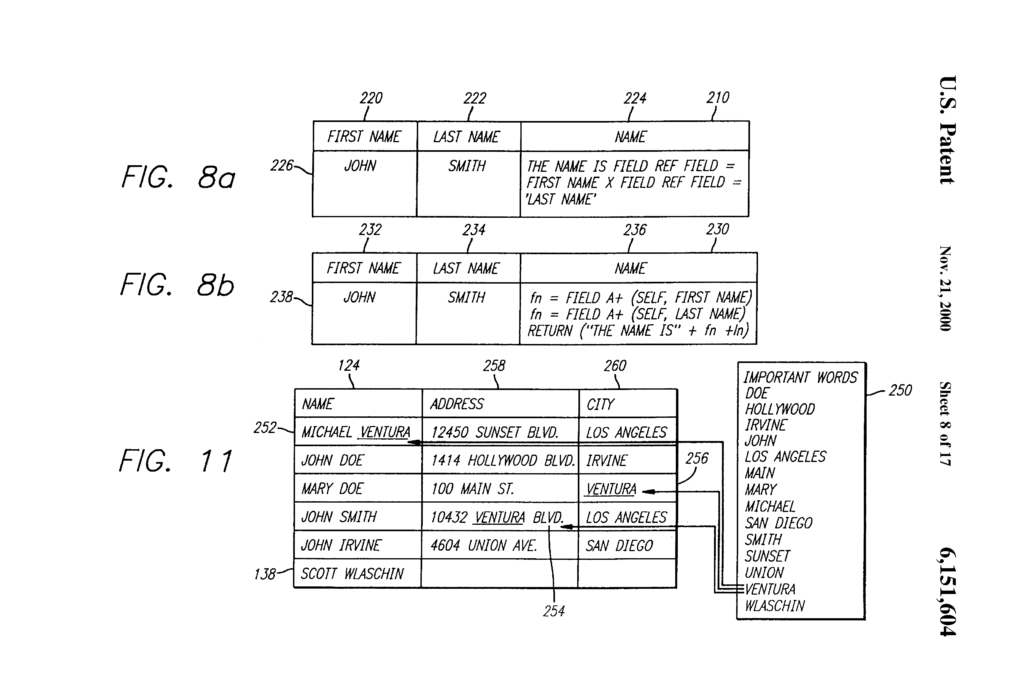

TLI Communications hold U.S. Patent No. 6,038,295 relating to a method and system for taking, transmitting, and organizing digital images. Enfish sued Microsoft for infringement of U.S. Patent 6,151,604 and U.S. Patent 6,163,775 related to a logical model for a computer database. A logical model is a model of data for a computer database explaining how the various elements of information are related to one another. A logical model generally results in the creation of particular tables of data, but it does not describe how the bits and bytes of those tables are arranged in physical memory devices. Contrary to conventional logical models, the patented logical model includes all data entities in a single table, with column definitions provided by rows in that same table. The patents describe this as a “self-referential” property of the database.

Enfish sued Microsoft for infringement of U.S. Patent 6,151,604 and U.S. Patent 6,163,775 related to a logical model for a computer database. A logical model is a model of data for a computer database explaining how the various elements of information are related to one another. A logical model generally results in the creation of particular tables of data, but it does not describe how the bits and bytes of those tables are arranged in physical memory devices. Contrary to conventional logical models, the patented logical model includes all data entities in a single table, with column definitions provided by rows in that same table. The patents describe this as a “self-referential” property of the database.