A system and method for determining eligibility for Social Security Disability Insurance benefits by computer is directed to steps that can be performed in the human mind, or by a human using a pen and paper and is therefore a patent-ineligible abstract idea.

A system and method for determining eligibility for Social Security Disability Insurance benefits by computer is directed to steps that can be performed in the human mind, or by a human using a pen and paper and is therefore a patent-ineligible abstract idea.

Killian appealed from a decision of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (Board) affirming the examiner’s rejection of all pending claims of U.S. Patent Application No. 14/450,042 under 35 U.S.C. § 101.

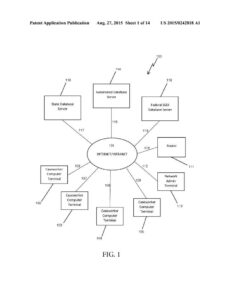

The application relates to a system and method for determining eligibility for Social Security Disability

Insurance [SSDI] benefits through a computer network. This process entails looking up information

from two sources: (1) a Federal Social Security database; and (2) a State database containing records for patients receiving treatment for developmental disabilities or mental illness. For those patients identified in the State database as meeting certain criteria but not currently receiving SSDI benefits, the method uses relevant

information to determine if a given patient is entitled to receive SSDI benefits. The specification explains that once the relevant information is on hand, the automated system seamlessly carries out the process of determining who is eligible for SSDI and who is not, which frees up assigned staff to perform more traditional duties.

Claim 1 is representative and recites:

A computerized method for determining overlooked eligibility for social security disability insurance

(SSDI)/adult child benefits through a computer network, the method comprising the steps of:

- (a) providing a computer processor and a computer readable media;

- (b) providing access to a Federal Social Security database through the computer network, wherein the Federal Social Security database provides records containing information relating to a person’s status of SSDI adult child benefits and/or parental and/or marital information relating to SSDI adult child benefit eligibility;

- (c) providing access to a State database through the network, wherein the State database provides records containing information relating to persons receiving treatment for developmental disabilities

and/or mental illness from a State licensed care facility; - (d) selecting at least one person from the State database who is identified as receiving treatment for developmental disabilities and/or mental illness;

(e) creating an electronic data record comprising information relating to at least the

identity of the person and social security number, wherein the electronic data record

is recorded on the computer readable media;

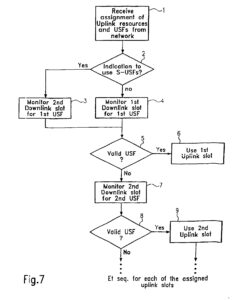

(f) retrieving the person’s Federal Social Security record containing information relating to the person’s status of SSDI adult child benefits through the network;

(g) determining whether the person is receiving SSDI adult child benefits based on the SSDI status information contained within the Federal Social Security database record through the computer network; - (h) indicating in the electronic data record whether the person is receiving SSDI adult

child benefits or is not receiving SSDI adult child benefits;

for at least one electronic data record of persons indicated as not receiving SSDI adult child benefits,

comprising the steps of:

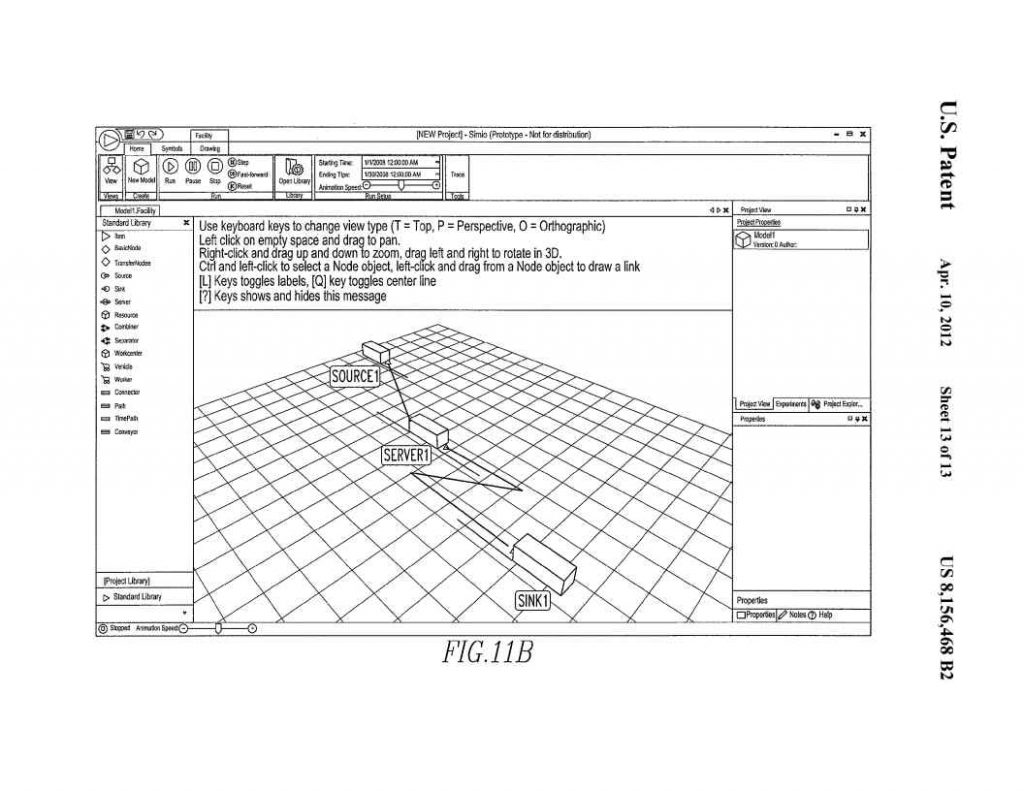

- (a) providing a caseworker display system;

- (b) generating a data collection input screen display to the caseworker display system relating to the electronic data record of persons indicated as not receiving SSDI adult child benefits;

- (c) caseworker identifying and inputting parental and/or marital names and Social

Security numbers into the electronic data record of the person indicated in the electronic data record as not receiving SSDI adult child benefits; - (d) retrieving parental and/or marital Social Security record(s) from the Federal Social Security database through the computer network in order to identify information for determining eligibility for SSDI adult child benefits;

- (e) determining whether the person indicated in the electronic data record is eligible for receiving SSDI adult child benefits based on the identified information for determining eligibility of SSDI adult child benefits and current SSDI benefit legal requirements; and

- (f) indicating in the electronic data record whether the person is eligible for SSDI adult child benefits or is not eligible for SSDI adult child benefits.

The examiner had rejected all pending claims of the application under 35 U.S.C. § 101, finding that they were directed to the abstract idea of “determining eligibility for social security disability insurance . . . benefits” and lacked additional elements amounting to significantly more than the abstract idea because the additional elements were simply generic recitations of generic computer functionalities.

In Alice, and Mayo Collaborative Services v. Prometheus Laboratories, Inc. (2012), the Supreme Court explicated a two-step test for determining whether claimed subject matter falls within one of the judicial exceptions to patent eligibility. First, the Federal Circuit is to determine whether the claims at issue are directed to a patent-ineligible concept, such as an abstract idea. Second, if the claims are directed to a patent-ineligible concept, the Federal Circuit is to examine the elements of the claim to determine whether it contains an inventive concept sufficient to transform the claimed abstract idea into a patent-eligible application.

According to the Federal Circuit, the claims of this patent application did not pass the two-step test. They said that, here, the focus of the claimed advance over the prior art shows that “the claim’s ‘character as a whole’ is directed to steps that can be performed in the human mind, or by a human using a pen and paper, so the claim is for a patent-ineligible abstract idea.

According to the Federal Circuit, the thrust of the application’s representative claim 1 is the collection of information from various sources (a Federal database, a State database, and a caseworker) and understanding the meaning of that information (determining whether a person is receiving SSDI benefits and determining whether they are eligible for benefits under the law). The Board correctly concluded that these steps can be performed by a human, using observation, evaluation, judgment, and opinion, because they involve making determinations and identifications, which are mental tasks humans routinely do.

That these steps, with the exception of the step of the caseworker obtaining additional information, are performed on a generic computer does not save the claims from being directed to an abstract idea. We have distinguished

between claims “directed to an improvement in the functioning of a computer,” versus those, like the claims at

issue here, that simply recite “generalized steps to be performed on a computer using conventional computer activity.”

An inventor of a new software program should carefully consider whether the invention can somehow be framed as an improvement in operation of a computer. If you need help protecting your software, contact Malhotra Law Firm, PLLC.

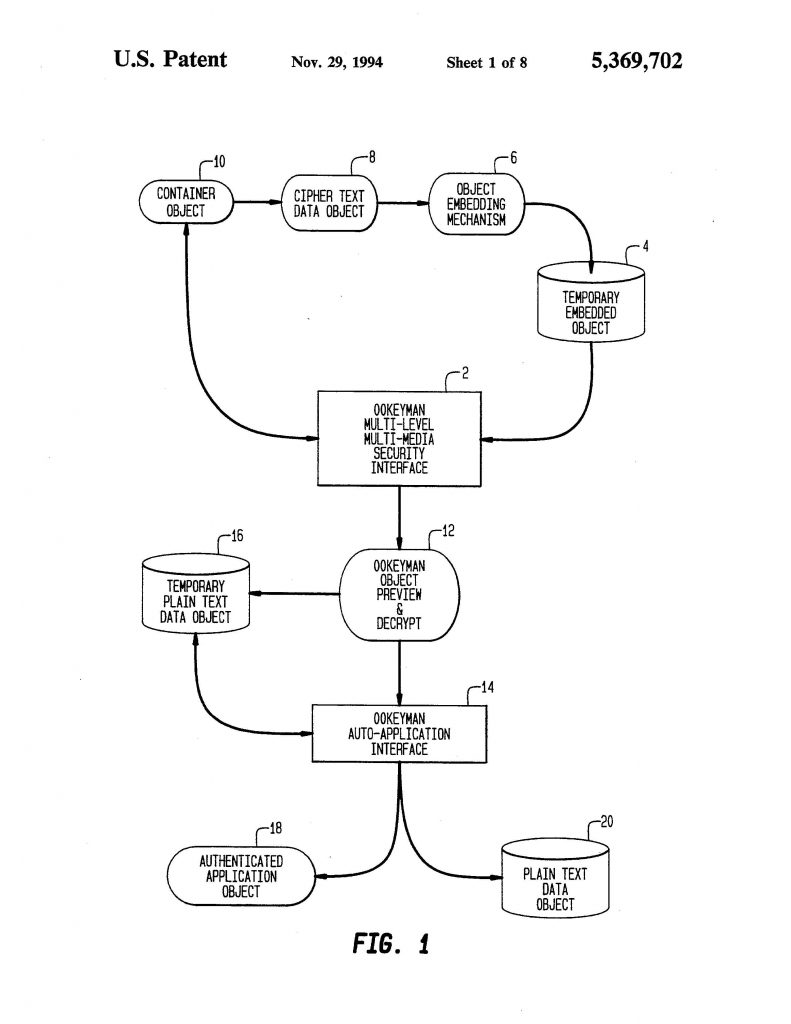

Multilevel security claims were patent eligible because they were directed to solving a technical problem specific to computer network security. The district court correctly rejected Adobe’s ineligibility challenge.

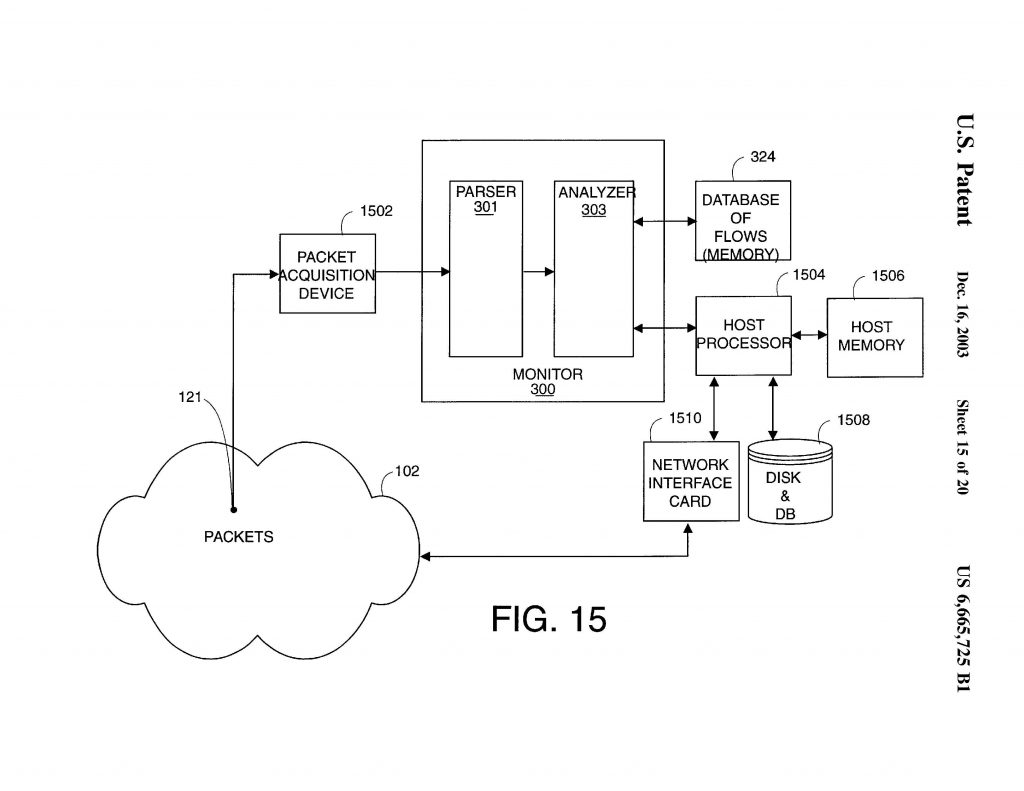

Multilevel security claims were patent eligible because they were directed to solving a technical problem specific to computer network security. The district court correctly rejected Adobe’s ineligibility challenge. NetScout Systems appealed from a judgment of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Texas which held that NetScout willfully infringed various claims of U.S. Patent No. 6,665,725; 6,839,751; and 6,954,789 and held that the claims were valid under 35 U.S.C. §101.

NetScout Systems appealed from a judgment of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Texas which held that NetScout willfully infringed various claims of U.S. Patent No. 6,665,725; 6,839,751; and 6,954,789 and held that the claims were valid under 35 U.S.C. §101.