TRINITY INFO MEDIA, LLC V. COVALENT, INC., FEDERAL CIRCUIT 2023 (SOFTWARE PATENTS)

Trinity Info Media, LLC sued Covalent, Inc. for infringement of U.S. Patent Nos. 9,087,321 and 10,936,685 relating to methods and systems for connecting users based on their answers to polling questions. U.S. Patent No. 9,087,321 teaches that its claimed invention is “directed to a poll-based networking system that connects users based on similarities as determined through poll answering and provides real-time results to the users. The claimed invention of the ’685 patent is “directed to a poll-based networking and ecommerce system that connects users to other users, or products, goods and/or services based on similarities as determined through poll answering and provides real-time results to the users.

Trinity Info Media, LLC sued Covalent, Inc. for infringement of U.S. Patent Nos. 9,087,321 and 10,936,685 relating to methods and systems for connecting users based on their answers to polling questions. U.S. Patent No. 9,087,321 teaches that its claimed invention is “directed to a poll-based networking system that connects users based on similarities as determined through poll answering and provides real-time results to the users. The claimed invention of the ’685 patent is “directed to a poll-based networking and ecommerce system that connects users to other users, or products, goods and/or services based on similarities as determined through poll answering and provides real-time results to the users.

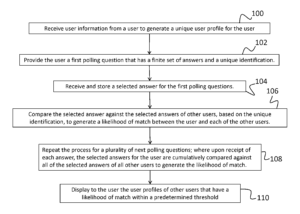

Claim 1 of U.S. Patent No. 9,087,321 is representative and recites:

1. A poll-based networking system, comprising:

- a data processing system having one or

more processors and a memory, the

memory being specifically encoded with instructions such that when executed, the instructions cause the one or more processors

to perform operations of:- receiving user information from a user to generate a unique user profile for the user;

- providing the user a first polling question, the first polling question having a finite set of answers and a unique identification;

- receiving and storing a selected answer for the first polling question;

- comparing the selected answer against the selected answers of other users, based on the unique identification, to generate a likelihood of match between the user and each of the other users; and

- displaying to the user the user profiles of other users that have a likelihood of match within a predetermined threshold.

Claim 2 of U.S. Patent No. 10,936,685 recites:

2. A computer-implemented method for creating a poll-based network, the method comprising an act of causing one or more processors having an associated memory specifically encoded with computer executable instruction means to execute the instruction means to cause the one or more processors to collectively perform operations of:

- receiving user information from a user to generate a unique user profile for the user;

- providing the user one or more polling

questions, the one or more polling questions having a finite set of answers and a unique identification; - receiving and storing a selected answer for the one or more polling questions;

- comparing the selected answer against the selected answers of other users, based on the unique identification, to generate a likelihood of match between the user and each of the other users;

- causing to be displayed to the user other users, that have a likelihood of match within a predetermined threshold;

- wherein one or more of the operations are carried out on a hand-held device; and wherein two or more results based on the likelihood of match are displayed in a list reviewable by swiping from one result to another.

Covalent filed a motion to dismiss Trinity’s complaint, arguing that the asserted claims are invalid under 35 U.S.C. § 101.

The Federal Circuit applied the two-step framework set forth in Mayo Collaborative Services v. Prometheus Laboratories, Inc., 566 U.S. 66, 77–80 (2012), and further detailed in Alice v. CLS. At step one, they “determine whether the claims at issue are directed to one of those patent-ineligible concepts” such as an abstract idea. At step two, they “consider the elements of each claim both individually and as an ordered combination to determine whether the additional elements transform the nature of the claim into a patent-eligible application.”

Considering step one, the Federal Circuit states that these independent claims are focused on “collecting information, analyzing it, and displaying certain results,” which places them in the “familiar class of claims ‘directed to’ a patent-ineligible concept.” A human mind could review people’s answers to questions and identify matches based on those answers. The Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that the independent claims of both patents are directed to an abstract idea, matching based on questioning.

The ’685 patent’s requirements that the abstract idea be performed on a “hand-held device” or that matches are “reviewable by swiping” does not alter our conclusion that the focus of the asserted claims remains directed to an abstract idea.

In the context of software-based inventions, Alice/Mayo step one “often turns on whether the claims focus on the specific asserted improvement in computer capabilities or, instead, on a process that qualifies as an abstract idea for which computers are invoked merely as a tool.”

The Federal Circuit next considered and rejected several arguments raised by Trinity as to why its claims are not directed to an abstract idea.

Trinity argued that the district court’s analysis at Alice/Mayo step one failed to appreciate several statements in its complaint demonstrating that the patents included an advance over the prior art, that the prior art did not carry out matching on mobile phone, that the prior art did not employ multiple match servers, and that the prior art did not employ match aggregators. These statements did not change the Federal Circuit’s analysis at Alice/Mayo step one. Even accepting these statements as true, the claims are directed to nothing more than performing the abstract idea of matching on a mobile phone according to the Federal Circuit.

Trinity also argued that humans could not mentally engage in the “same claimed process” because they could not perform “nanosecond comparisons” and aggregate “result values with huge numbers of polls and members,” nor could they select criteria using “servers, storage, identifiers, and/or thresholds. The Federal Circuit did not accept this argument because the patent claims did not require such nanosecond comparisons or aggregating huge numbers of polls and members. A practice tip, then, would be if you plan to argue that computers can do certain things that humans can’t, put the advantages in the claims.

Similarly, a human could not communicate over a computer network without the use of a computer, yet the Federal Circuit previously held that claims directed to enabling “communication over a network” were focused on an abstract idea in ChargePoint v Semaconnect.

Trinity compared this case to other decisions where the Federal Circuit found the patented invention to be directed to improvements to the functionality of a computer or network platform itself. However, Trinity used generic computing terms in the patents.

Trinity further argued that the district court failed to adequately consider comparing a selected answer against other users “based on the unique identification,” which

Trinity asserts was a “non-traditional design” that allowed for “rapid comparison and aggregation of result values even with large numbers of polls and members.” The Federal Circuit disagreed. The use of a unique identifier does not prevent a claim from being directed to an abstract idea.

Trinity also pointed to the use of “match servers” and “a match aggregator” to identify matches. Of the asserted claims, only dependent claim 8 of the ’321 patent requires that processors be configured to perform operations involving a “match aggregator” and

“web server” and storing “answers in a database.” According to the Federal Circuit, these components merely place the abstract idea in the context of a distributed networking system, which in the context of the claimed invention as described in the specification does not change the focus of the asserted claims from an abstract idea.

Trinity argued that the district court omitted the limitation of generating a likelihood of match “within a predetermined threshold,” without which “there would be

no limit or logic associated with the volume or type of results a user would receive.” The Federal Circuit was not convinced that this limitation changes the focus of the claimed invention to something other than the abstract idea of matching based on questioning. Indeed, this limitation merely reflects the kind of data analysis that the abstract idea of matching necessarily includes (e.g., how many answers should be the same before declaring a match).

In conclusion, the asserted claims are directed to the abstract idea of matching based on questioning at Step One.

At Alice/Mayo step two, we “consider the elements of [the] claim both individually and ‘as an ordered combination’ to determine whether the additional elements ‘transform the nature of the claim’ into a patent-eligible application.”

Trinity argued that the district court failed to consider allegations in its complaint that several features of the asserted claims were not “well-understood, routine

or conventional,” listing features purportedly not present in the prior art. Taken as an ordered combination, Trinity argued that claim 1 of the ’321 patent and claim

2 of the ’685 patent contain an inventive concept because they recite steps performed in a “non-traditional system” that can “rapidly connect multiple users using progressive

polling that compare[s] answers in real time based on their unique identification (ID) (and in the case of the ’685 patent employ swiping).” Trinity also argued that dependent claims 2, 3, 8, and 19 of the ’321 patent contain an inventive concept because they specify matching based on “all polls the user previously answered (based on unique identifications)” and include hardware components, “including a server, a database, a match aggregator and a plurality of match servers.”

However, according to the Federal Circuit, claiming the improved speed or efficiency inherent with applying the abstract idea on a computer is insufficient to render the claims patent eligible as an improvement to computer functionality. Here, the asserted claims are organized in an expected way—receiving user information, asking that user questions, receiving answers, identifying and displaying a match based on those answers.

The Federal Circuit has “ruled many times” that “invocations of computers and networks that are not even arguably inventive are insufficient to pass the test of an inventive concept in the application of an abstract idea.”

The Federal Circuit’s conclusion was made easier by the fact that the ’321 patent teaches the use of “conventional” processors, the use of a “web server computer 804” that can be a “conventional server computer system” inclusive of the “match aggregator and/or match server,” and that “[t]he physical connections of the Internet and the protocols and communication procedures of the Internet are well known to those of skill in the art.”

The Federal Circuit was also not persuaded by Trinity’s argument that certain claims contain an inventive concept because they are performed on a handheld device, use a matching application, or permit review of matches using swiping. Appellant’s Br. 32. Just as a claim is not rendered patent eligible by stating an abstract idea and instructing “apply it on a computer,” a claim is not rendered patent eligible merely because the abstract idea is applied on a handheld device or using a mobile application.

The asserted claims were found to be patent ineligible under § 101.