HAWK TECHNOLOGY SYSTEMS, LLC, V CASTLE RETAIL, LLC, FEDERAL CIRCUIT 2023 (SOFTWARE PATENTS)

A multi-format digital video product system capable of maintaining full-bandwidth resolution while providing professional quality editing and manipulation of images, which is capable of conserving bandwidth while preserving data is not patent-eligible.

A multi-format digital video product system capable of maintaining full-bandwidth resolution while providing professional quality editing and manipulation of images, which is capable of conserving bandwidth while preserving data is not patent-eligible.

Appellant Hawk Technology Systems, LLC sued Appellee Castle Retail, LLC in the Western District of Tennessee for patent infringement based on Castle Retail’s use of security surveillance video operations in its grocery stores. Castle Retail moved to dismiss under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6) for failure to state a claim.

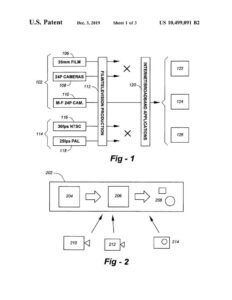

Hawk is the owner of U.S. Patent No. 10,499,091 titled “High-Quality, Reduced Data Rate Streaming Video Product and Monitoring System.” The patent relates to a method of viewing multiple simultaneously displayed and stored video images on a remote viewing device of a video surveillance system that has multiple cameras, a broadband connection, a server 312, and a monitor control system. The signals from the cameras are transmitted as streaming sources at relatively low data rates and variable frame rates via a broadband connection. This results in reduced costs to the user, lower memory storage requirements, and the ability to handle a larger monitoring application (due to bandwidth efficiency). This configuration uses existing broadband infrastructures and a generic PC-based server.

Claim 1 is representative and recites:

1. A method of viewing, on a remote viewing device of a video surveillance system, multiple simultaneously displayed and stored video images, comprising the steps of:

- receiving video images at a personal computer based system from a plurality of video sources, wherein each of the plurality of video sources comprises a camera of the video surveillance system;

- digitizing any of the images not already in digital form using an analog-to-digital converter;

- displaying one or more of the digitized images in separate windows on a personal computer based display device, using a first set of temporal and spatial parameters associated with each image in each window;

- converting one or more of the video source images into a selected video format in a particular resolution, using a second set of temporal and spatial parameters associated with each image;

- contemporaneously storing at least a subset of the converted images in a storage device in a network environment;

- providing a communications link to allow an external viewing device to access the storage device;

- receiving, from a remote viewing device remoted located remotely from the video surveillance system, a request to receive one or more specific streams of the video images;

- transmitting, either directly from one or more of the plurality of video sources or from the storage device over the communication link to the remote viewing device, and in the selected video format in the particular resolution, the selected video format being a progressive video format which has a frame rate of less than substantially 24 frames per second using a third set of temporal and spatial parameters associated with each image, a version or versions of one or more of the video images to the remote viewing device, wherein the communication link traverses an external broadband connection between the remote computing device and the network environment; and

- displaying only the one or more requested specific streams of the video images on the remote computing device.

Castle Retail moved to dismiss under Rule 12(b)(6) based on its assertion that the patent was invalid under 35 U.S.C. § 101. It argued that the patent claims failed the two-step analysis set forth in Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank International, 573 U.S. 208 (2014). The claims, it asserted, failed Alice step one because they are directed to the “abstract concept” of “collecting, manipulating, displaying, and storing information,” and failed Alice step two because they provide “conventional components” that “provide no inventive concept.”

The District Court found that even using Hawk’s description of the limitations, it is not clear how the claims do more than take video surveillance and digitize it for display and storage in a conventional computer system.” And it explained that surveillance monitoring has been a part of business practices since video cameras have been available. It also explained that, although Hawk identified the “temporal and spatial parameters” as the inventive concept and argued that “converting the data using” those “parameters” changes the nature of the data, neither the claims nor the specification “explain what those parameters are or how they should be manipulated.” As for Alice step two, the district court explained that the claimed “analog-to-digital converter” and “personal computer based system” “are not technological improvements but rather generic computer elements” and that the “parameters and frame rate, considering how they are defined in the claims and specification, similarly, do not appear to be more than manipulating data (in this case, images) in such a way that has been found to be abstract. The district oddly held a hearing and considered some evidence prior to deciding the R.12(b)(6) motion even though such motions are supposed to be based on the pleadings.

Section 101 of the Patent Act states: “Whoever invents or discovers any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof, may obtain a patent therefor, subject to the conditions and requirements of this title.” 35 U.S.C.§ 101. But § 101 “contains an important implicit exception: Laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas are not patentable.” Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank Int’l, 573 U.S. 208, 216 (2014). Of course, all inventions rely on laws of nature to some extent.

With regard to Alice step 1, the Federal Circuit agreed with the District Court that the patent is directed to the abstract idea of video storage and display. The claims are similar to those that the Federal Circuit has found to be directed to abstract ideas. For example, they held that “encoding and decoding image data and . . . converting formats, including when data is received from one medium and sent along through another, are by themselves abstract ideas.” Adaptive Streaming Inc. v. Netflix, Inc. 836 F. App’x 900, 903 (Fed. Cir. 2020).

(I would like to take this opportunity to provide you with an important hint in how to argue against Alice rejections. Attack the first step. Make sure that the claim is fairly analogized to an existing case finding something abstract. If the examiner can’t point to a similar situation where a claim was found to be abstract, point this out. Also be aware that, typically, the examiners will over-generalize.)

Hawk argued that the patent claims are directed not to an abstract idea but to “a solution to a technical problem, specifically a multi-format digital video product system capable of maintaining full-bandwidth resolution while providing professional quality editing and manipulation of images.” According to Hawk, the technical problem is “conserving bandwidth while preserving data” and that this solution is a “specific

implementation,” which can be achieved “by performing special data conversion of the video streams” and by digitizing and converting data to “change the nature of the data.”

According to the Federal Circuit, Hawk’s arguments fail because the claims themselves do not disclose performing any “special data conversion” or otherwise describe how the alleged goal of “conserving bandwidth while preserving data” is achieved. Nor do the claims (or the specification) explain what the claimed parameters are or how they should be manipulated. Stated otherwise, the patent claims lack sufficient recitation of how the purported invention improves the functionality of video surveillance systems and are recited at such a level of result-oriented generality that those claims amount to a mere implementation of an abstract idea.

To reduce the risk of Alice problems, Malhotra Law Firm PLLC suggests providing some detail in both the claims and specification, not just claiming the desired result.

Regarding Alice Step 2, Hawk argued that the claims recite an inventive solution—one “that achieves . . . the benefit of transmitting the same digital image to different devices for different and perhaps divergent purposes, while using the same bandwidth,” and that “reference[s] specific tools (such as an analog-to-digital converter, where necessary), specific parameters (such as three different sets of temporal and spatial parameters), and even specific frame rates (such as 24 frames per second).

The parameters were the best argument that Hawk had since Hawk admitted that the hardware recited in the claims was conventional. The Federal Circuit recognized that the claims include “parameters,” but the claims fail to specify precisely what the parameters are and the parameters at most concern abstract data manipulation—image formatting and compression.

The Federal Circuit did not see anything inventive in the ordered combination of the claim limitations. Merely reciting an abstract idea performed on a set of generic computer components, as the claims do here, would not contain an inventive concept.

Try to disclose and recite detail in the claims if possible. This may go against your nature if you normally try to obtain the broadest claims possible. If you need help protecting your software, contact Malhotra Law Firm, PLLC.