Enfish v Microsoft, Federal Circuit 2016 (Software Patents)

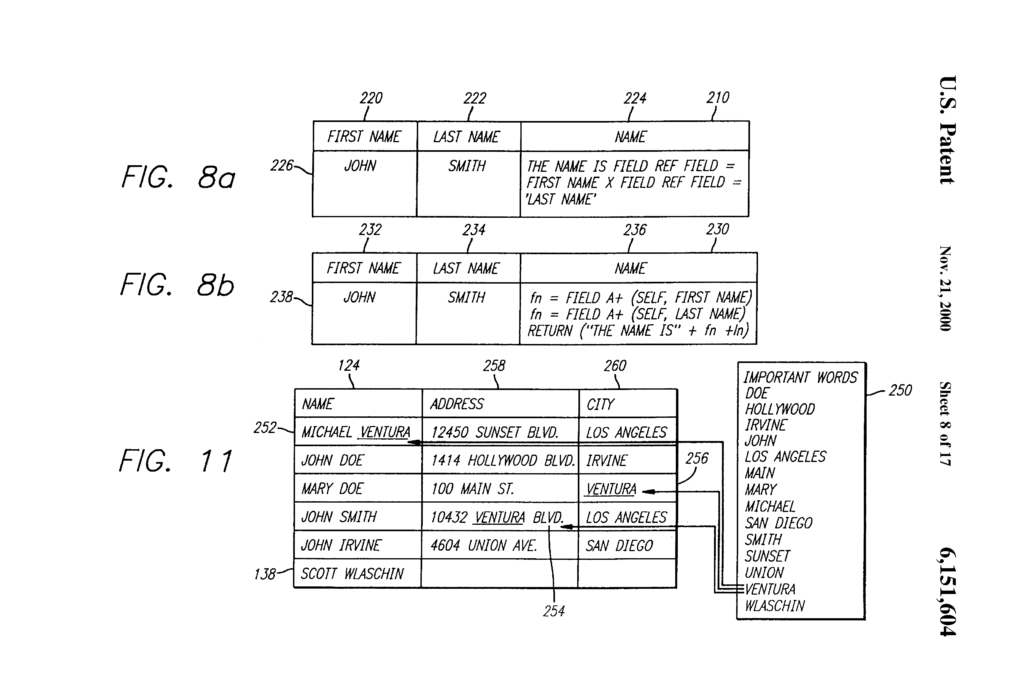

Enfish sued Microsoft for infringement of U.S. Patent 6,151,604 and U.S. Patent 6,163,775 related to a logical model for a computer database. A logical model is a model of data for a computer database explaining how the various elements of information are related to one another. A logical model generally results in the creation of particular tables of data, but it does not describe how the bits and bytes of those tables are arranged in physical memory devices. Contrary to conventional logical models, the patented logical model includes all data entities in a single table, with column definitions provided by rows in that same table. The patents describe this as a “self-referential” property of the database.

Enfish sued Microsoft for infringement of U.S. Patent 6,151,604 and U.S. Patent 6,163,775 related to a logical model for a computer database. A logical model is a model of data for a computer database explaining how the various elements of information are related to one another. A logical model generally results in the creation of particular tables of data, but it does not describe how the bits and bytes of those tables are arranged in physical memory devices. Contrary to conventional logical models, the patented logical model includes all data entities in a single table, with column definitions provided by rows in that same table. The patents describe this as a “self-referential” property of the database.

This self-referential property can be best understood in contrast with the more standard “relational” model. With the relational model, each entity (i.e., each type of thing) that is modeled is provided in a separate table. For instance, a relational model for a corporate file repository might include the following tables:

document table,

person table,

company table.

The document table might contain information about documents stored on the file repository, the person table might contain information about authors of the documents, and the company table might contain information about the companies that employ the persons.

In contrast to the relational model, the patented self referential model has two features that are not found in the relational model: first the self-referential model can store all entity types in a single table, and second the self-referential model can define the table’s columns by rows in that same table.

Claim 17 of the ’604 patent recites:

A data storage and retrieval system for a computer memory, comprising:

means for configuring said memory according to a logical table, said logical table including:

a plurality of logical rows, each said logical row including an object identification number (OID) to identify each said logical row, each said logical row corresponding to a record of information;

a plurality of logical columns intersecting said plurality of logical rows to define a plurality of logical cells, each said logical column including an OID to identify each said logical column; and

means for indexing data stored in said table.

The Federal Circuit reviewed de novo the district court’s determination that the claims at issue do not claim patent-eligible subject matter.

Section 101 of the patent act provides that a patent may be obtained for “any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof.” 35 U.S.C. § 101. The Federal Circuit noted that they, as well as the Supreme Court, have long grappled with the exception that “[l]aws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas are not patentable.” Ass’n for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics, Inc., — U.S. —-, 133 S. Ct. 2107, 2116 (2013) (quoting Mayo Collaborative Servs. v. Prometheus Labs., Inc., — U.S. —-, 132 S. Ct. 1289, 1293 (2012)).

The Federal Circuit noted that Supreme Court precedent instructs them to “first determine whether the claims at issue are directed to a patent-ineligible concept.” Alice Corp. Pty Ltd. v. CLS Bank Int’l. If this threshold determination is met, we move to the second step of the inquiry and “consider the elements of each claim both individually and ‘as an ordered combination’ to determine whether the additional elements ‘transform the nature of the claim’ into a patent-eligible application.” Id. (quoting Mayo, 132 S. Ct. at 1298, 1297).

The Supreme Court has not established a definitive rule to determine what constitutes an “abstract idea” sufficient to satisfy the first step of the Mayo/Alice inquiry.

Rather, both the Federal Circuit and the Supreme Court have found it sufficient to compare claims at issue to those claims already found to be directed to an abstract idea in previous cases.

Refreshingly, the Federal Circuit in Enfish stated that: “We do not read Alice to broadly hold that all improvements in computer-related technology are inherently abstract and, therefore, must be considered at step two. Indeed, some improvements in computer-related technology when appropriately claimed are undoubtedly not abstract, such as a chip architecture, an LED display, and the like. Nor do we think that claims directed to software, as opposed to hardware, are inherently abstract and therefore only properly analyzed at the second step of the Alice analysis. Software can make non-abstract improvements to computer technology just as hardware improvements can, and sometimes the improvements can be accomplished through either route. We thus see no reason to conclude that all claims directed to improvements in computer-related technology, including those directed to software, are abstract and necessarily analyzed at the second step of Alice, nor do we believe that Alice so directs. Therefore, we find it relevant to ask whether the claims are directed to an improvement to computer functionality versus being directed to an abstract idea, even at the first step of the Alice analysis.”

The Federal Circuit stated that, for that reason, the first step in the Alice inquiry in this case asks whether the focus of the claims is on the specific asserted improvement in computer capabilities (i.e., the self-referential table for a computer database) or, instead, on a process that qualifies as an “abstract idea” for which computers are invoked merely as a tool.

The Federal Circuit concluded that in this case, the plain focus of the claims is on an improvement to computer functionality itself, not on economic or other tasks for which a computer is used in its ordinary capacity. Therefore, it was not necessary to proceed to step two of the Mayo analysis.

Accordingly, the Federal Circuit found in this case, that the claims at issue in this appeal are not directed to an abstract idea within the meaning of Alice. Rather, they are directed to a specific improvement to the way computers operate, embodied in the self-referential table.

The district court had concluded that the claims were directed to the abstract idea of “storing, organizing, and retrieving memory in a logical table” or, more simply, “the concept of organizing information using tabular formats.”

However, describing the claims at such a high level of abstraction and untethered from the language of the claims all but ensures that the exceptions to § 101 swallow the rule. See Alice (noting that “we tread carefully in construing this exclusionary principle [of laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas] lest it swallow all of patent law”); cf. Diamond v. Diehr (cautioning that overgeneralizing claims, “if carried to its extreme, make[s] all inventions unpatentable because all inventions can be reduced to underlying principles of nature which, once known, make their implementation obvious”).

Here, the claims are not simply directed to any form of storing tabular data, but instead are specifically directed to a self-referential table for a computer database. For claim 17, this is reflected in step three of the “means for configuring” algorithm described above.

Moreover, the Federal Circuit was not persuaded that the invention’s ability to run on a general-purpose computer dooms the claims. Unlike the claims at issue in Alice or, more recently in Versata Development Group v. SAP America, Inc., 793 F.3d 1306 (Fed. Cir. 2015), the claims here are directed to an improvement in the functioning of a computer. In contrast, the claims at issue in Alice and Versata can readily be understood as simply adding conventional computer components to well-known business practices.

The Federal Circuit also noted that the fact that an improvement is not defined by reference to “physical” components does not doom the claims. To hold otherwise risks resurrecting a bright-line machine-or-transformation test, cf. Bilski v. Kappos (“The machine-or-transformation test is not the sole test for deciding whether an invention is a patent-eligible ‘process.’”), or creating a categorical ban on software patents, cf. id. at 603. Much of the advancement made in computer technology consists of improvements to software that, by their very nature, may not be defined by particular physical features but rather by logical structures and processes. The Federal Circuit did not see in Bilski or Alice, or our cases, an exclusion to patenting this large field of technological progress.

The Federal Circuit went on to say that, in other words, they were not faced with a situation where general-purpose computer components are added post-hoc to a fundamental economic practice or mathematical equation. Rather, the claims are directed to a specific implementation of a solution to a problem in the software arts. Accordingly, the Federal Circuit found the claims at issue were not directed to an abstract idea.

Because the claims were not directed to an abstract idea under step one of the Alice/Mayo analysis, the Federal Circuit did not need to proceed to step two of that analysis.

The Federal Circuit concluded that the claims were patent-eligible under 35 USC 101.